Femur

Fracture

- Home

- Conditions We Treat

- Knee

- Femur Fracture

Introduction

A femur fracture is one of the most serious bone injuries a person can sustain. The femur, or thigh bone, is the largest, heaviest and strongest bone in the human body, built to support the entire body’s weight during movement. Breaking it requires a significant force, which is why femur fractures are most often linked to severe accidents such as high-speed road collisions, falls from height, or major sports injuries.

Because this injury can cause massive internal bleeding, severe pain and long-term mobility problems, it demands immediate medical attention. Timely diagnosis, prompt treatment and structured rehabilitation are essential for restoring function and preventing complications.

What is a femur fracture?

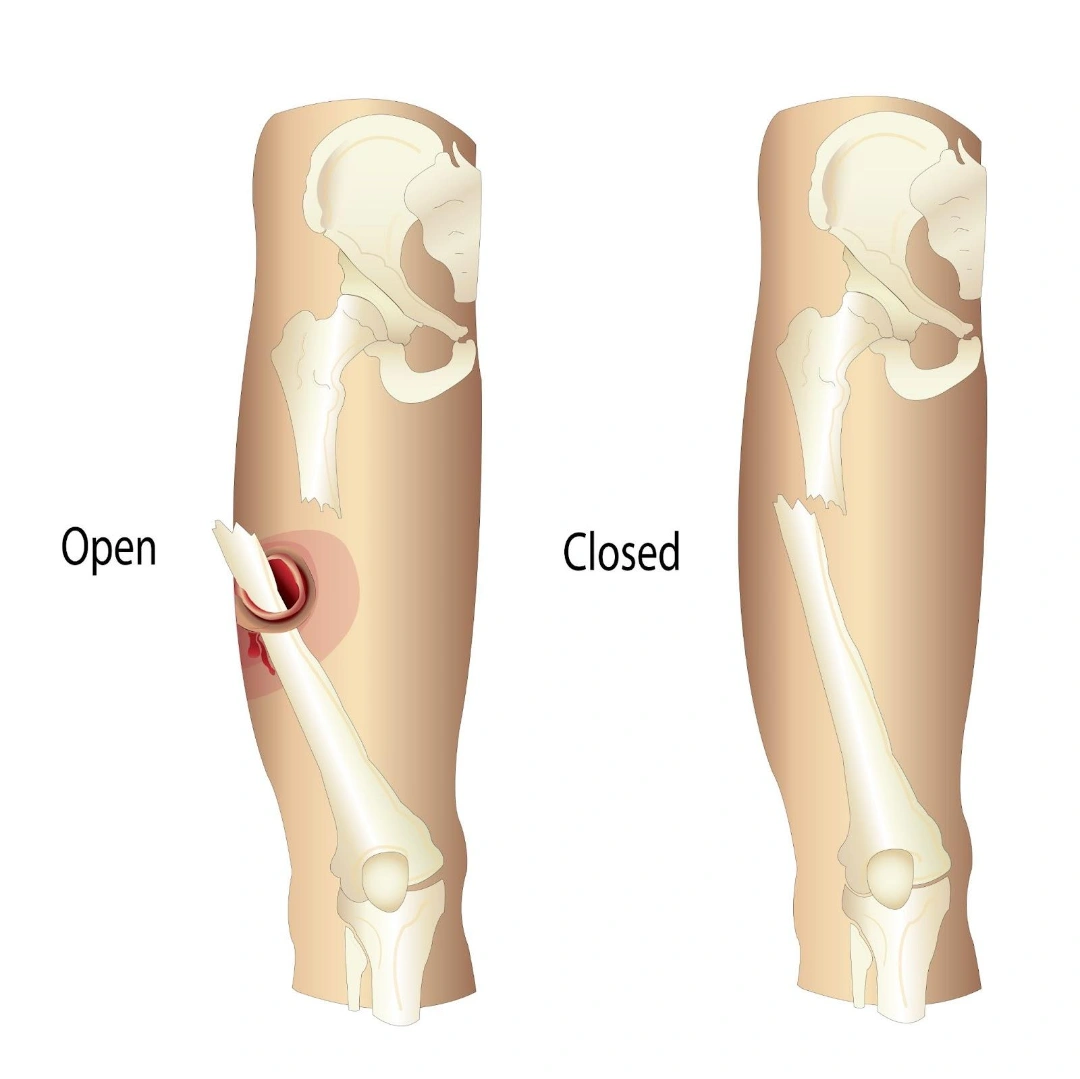

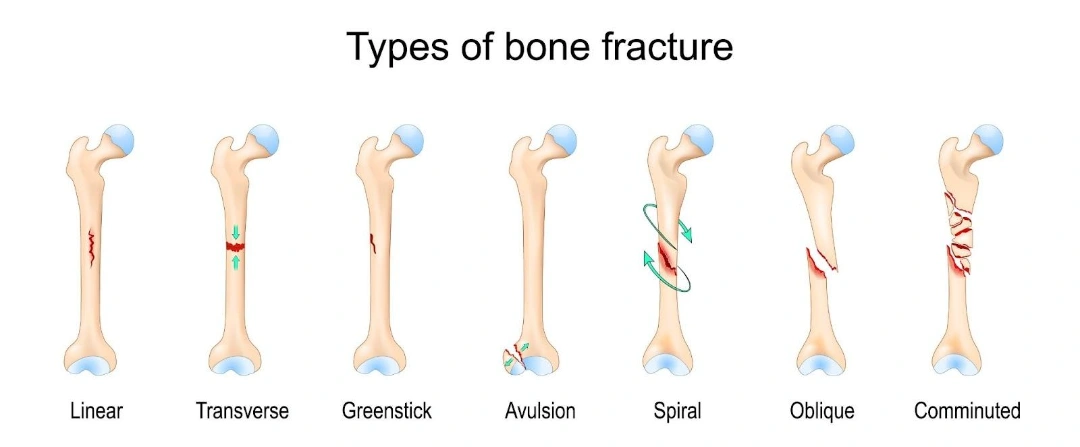

A femur fracture occurs when there is a complete or partial break in the thigh bone. Depending on where it happens, a fracture may affect the hip joint (proximal femur), the shaft (mid-section), or the area near the knee (distal femur). The severity can range from a clean break to multiple shattered fragments, and each type requires a different approach to treatment and recovery.

The femur — structure and function

Understanding the anatomy of the femur helps explain why fractures here are so significant.

- Proximal femur — the upper end forms part of the hip joint, including the femoral head, neck and bony prominences called the greater and lesser trochanters. These areas play a key role in hip mobility and weight transfer.

- Femoral shaft — the long, slightly curved middle section, built to absorb stress during walking, running and jumping. Its thick structure makes it extremely strong, but also means a fracture here usually results from high-energy trauma.

- Distal femur — the lower end widens into two rounded condyles, which form part of the knee joint. Fractures in this area often extend into the joint, requiring precise reconstruction to protect long-term knee function.

Because the femur is central to movement and load-bearing, any break has a profound impact on mobility and quality of life.

Classification of femur fracture

Femur fractures are often classified using the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen/Orthopaedic Trauma Association (AO/OTA) classification.

| Femur shaft fracture (32) | Description | Sub-classification |

|---|---|---|

| 32A | Simple | 1 - Spiral |

| 2 - Oblique, angle > 30° | ||

| 3 - Transverse, angle < 30° | ||

| 32B | Wedged | 1 - Spiral wedge |

| 2 - Bending wedge | ||

| 3 - Fragmented wedge | ||

| 32C | Complex | 1 - Spiral |

| 2 - Segmental | ||

| 3 - Irregular |

Another type of femur fracture classification is the Winquist and Hansen classification, which classifies the injury based on comminution (when a bone breaks and splinters into many small fragments/segments) and stability of the femur.

| Femur fracture type | Description |

|---|---|

| Type 0 | No comminution |

| Type I | Small amount of comminution, < 25% of the width of the bone |

| Type II | Butterfly fragment, ≤ 50% of the width of the bone |

| Type III | Comminution with large butterfly fragment, > 50% of the width of the bone |

| Type IV | Segmental fracture, with no contact of proximal and distal fragments |

These classification methods can be used together to assess the severity of the injury and assist orthopaedic surgeons in determining the most appropriate treatment approach.

What causes a femur fracture?

Femur fractures occur when a force overwhelms the bone’s strength. In healthy bone, this usually requires a high-impact event; in weakened bone, even a minor fall can cause a break.

High-energy causes include:

- Road traffic accidents — common in car, motorcycle and pedestrian collisions, where sudden impact or compression forces cause the bone to snap.

- Falls from height — landing on the feet or side can transmit enough force up the leg to fracture the femur.

- Sports injuries — high-speed or contact sports like skiing, rugby and extreme cycling can create twisting or bending forces that break the bone.

- Crush injuries — heavy machinery accidents or building collapses can cause severe, often open, fractures.

- Gunshot wounds — the energy from a bullet can shatter bone and damage surrounding tissue.

Low-energy causes include:

- Osteoporosis — a condition that weakens bones, making them more prone to breaking from a simple trip or minor fall.

- Pathological fractures — caused by underlying bone diseases, such as cancer or infection, which compromise bone strength.

What are the symptoms of a femur fracture?

Femur fractures cause severe, unmistakable symptoms that require urgent medical evaluation

- Intense thigh pain — immediate and severe, worsens with any movement.

- Inability to bear weight — standing or walking is typically impossible.

- Swelling and bruising — rapid onset due to bleeding within the thigh muscles.

- Visible deformity — the leg may appear shortened, outwardly rotated, or bent.

- Open wound with bone exposure — in open fractures, bone fragments may pierce the skin, increasing infection risk.

- Signs of shock — pale skin, rapid heartbeat and dizziness due to internal bleeding.

Who is most at risk of a femur fracture in Singapore?

While a femur fracture can happen to anyone given enough force, certain groups face a significantly higher risk due to lifestyle, health conditions or age-related changes in bone strength.

- Young adults, particularly men — this group is more likely to be involved in high-speed motor vehicle accidents, motorcycle crashes, or high-intensity sports. Their activity levels and exposure to risky situations make them more prone to the high-energy trauma that typically causes femoral shaft fractures.

- Older adults, especially postmenopausal women — Osteoporosis weakens bone structure over time, reducing the force required to cause a break. In this group, even a simple fall from standing height can lead to a femoral neck or intertrochanteric fracture, which often requires surgery to restore mobility and prevent long-term disability.

- Athletes in high-impact or collision sports — participants in sports such as skiing, rugby, motocross and downhill cycling are regularly exposed to twisting forces, sudden decelerations and high-impact collisions. These movements can place extreme stress on the femur, increasing the likelihood of fractures, particularly in the shaft or distal regions.

- People with underlying bone disease — conditions such as metastatic bone cancer, osteogenesis imperfecta (brittle bone disease), or chronic bone infections weaken the bone’s internal structure. In these cases, even minimal trauma can cause a pathological fracture and management often requires addressing the underlying disease as part of the treatment plan.

How is a femur fracture diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves confirming the fracture, assessing its complexity and identifying any related injuries.

- Physical examination — the doctor inspects for deformity, swelling, bruising, open wounds and checks circulation and nerve function in the leg.

- X-rays — standard imaging to confirm the fracture’s location, type and alignment. Usually includes the hip and knee joints to detect associated injuries.

- CT scans — provide a detailed view of complex fractures, especially those involving joints and help plan surgery.

- MRI scans — occasionally used to assess surrounding soft tissue injuries or detect subtle fractures not seen on X-ray.

- Vascular studies — doppler ultrasound or CT angiography may be needed if blood vessel injury is suspected.

What complications can occur after a femur fracture?

A femur fracture is a serious injury, and even with expert care, complications can arise. Recognising these risks early is key to prevention and timely management.

- Nonunion or delayed union — healing is slower than expected or fails to occur, often due to poor blood supply, infection, or severe fracture patterns. Management may involve bone grafting, revision fixation, or techniques to stimulate healing.

- Malunion — the bone heals in an incorrect position, causing leg length differences, altered gait, or abnormal alignment. In some cases, corrective surgery (osteotomy) may be needed to restore normal function.

- Infection — more common in open fractures or after surgery, infections may be superficial or deep (osteomyelitis). Treatment includes antibiotics, wound care and sometimes surgical cleaning or implant removal.

- Fat embolism syndrome — fat droplets released from the bone marrow can enter the bloodstream, potentially reaching the lungs or brain. This can cause breathing problems, confusion and skin changes, and requires immediate hospital care.

- Joint stiffness — particularly in knee-involving distal femur fractures, stiffness can occur if early mobilisation is delayed. Physiotherapy and, in some cases, additional surgical intervention may be necessary.

- Nerve or blood vessel injury — can occur during the injury itself or as a rare complication of surgery. Urgent assessment and repair may be needed to preserve limb function.

Can a femur fracture be prevented?

Not all trauma can be avoided, but certain measures can lower the risk of sustaining a femur fracture and improve bone resilience.

- Practice road safety — always wear seatbelts, follow speed limits and use appropriate protective gear when riding motorcycles or bicycles.

- Use sports protection — in high-impact sports, wear recommended protective equipment and follow safety guidelines to reduce injury risk.

- Maintain strong bones — ensure adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, engage in weight-bearing exercise and address nutritional deficiencies promptly.

- Treat osteoporosis early — screening and medication can significantly reduce fracture risk in older adults, especially postmenopausal women.

- Reduce fall hazards — keep living spaces free of clutter, improve lighting and install handrails where needed to prevent falls.

What are the treatment options for a femur fracture in Singapore?

Most femur fractures require surgery because of the bone’s size, strength and role in weight-bearing. Non-surgical management is rare and only suitable for specific stable fractures or patients unfit for surgery.

- Non-surgical management of a femur fracture

Non-surgical treatment is rare and only considered in very specific situations, typically when the fracture is stable, non-displaced, or when a patient’s health status makes surgery too risky. The goal is to allow the bone to heal in proper alignment while avoiding further injury.

- Casting or bracing — a full-length cast or rigid brace immobilises the hip, knee and ankle to prevent movement at the fracture site. This method can be effective for certain distal femur fractures or stable hairline cracks but requires strict patient compliance. Prolonged immobilisation may result in joint stiffness, muscle loss and longer rehabilitation times.

- Skeletal traction — pins or wires are inserted into the bone above or below the fracture and weights are applied to gently pull the bone into correct alignment. Traction is often used as a temporary measure before surgery or when surgery isn’t immediately possible. It can reduce pain, maintain bone length and prevent further soft tissue damage while awaiting definitive treatment.

While these methods can achieve healing in select cases, most femur fractures benefit from surgical fixation to allow earlier movement and reduce the risk of complications.

2. Surgical management of a femur fracture

Surgery is the standard of care for most femur fractures, providing stability, restoring alignment and enabling early rehabilitation. The choice of technique depends on fracture location, pattern and patient factors.

- Intramedullary nailing — a long metal rod is inserted into the bone’s central canal (either from the hip or knee end) and locked in place with screws. This technique is used for most femoral shaft fractures because it provides excellent stability, allows earlier weight-bearing and minimises disruption to surrounding soft tissues.

- Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) — the fracture is surgically exposed, carefully realigned, and secured with plates and screws. ORIF is often preferred for fractures near joints, multi-fragment injuries, or patterns where a nail is unsuitable. This approach offers precise anatomical restoration, especially important for joint-involving distal or proximal fractures.

- External fixation — metal pins or screws are inserted into the bone above and below the fracture, then connected to a rigid external frame. This method is typically used as a temporary stabilisation in severe open fractures, cases with significant soft tissue injury, or unstable patients who are not immediately fit for major surgery.

- Plate fixation — specially contoured plates are attached to the bone with screws, providing rigid support along the fracture site. Plate fixation is common in distal femur fractures, periprosthetic fractures (around an existing implant), or cases where fracture geometry does not permit intramedullary nailing.

Summary

A femur fracture is one of the most severe orthopaedic injuries, involving a break in the thigh bone, the strongest bone in the human body. It often results from high-energy trauma such as road accidents, falls from height, or sports collisions, but in people with weakened bones, even minor falls can cause it. Symptoms typically include intense thigh pain, inability to bear weight, swelling, bruising, and sometimes visible deformity.

Diagnosis relies on a thorough clinical examination supported by imaging, with X-rays and, in complex cases, CT or MRI scans. Most femur fractures require surgical stabilisation using techniques such as intramedullary nailing, plate fixation, or external fixation, though non-surgical options may be considered in rare, stable cases. Recovery involves a carefully planned rehabilitation programme to restore mobility, strength and function, while minimising the risk of complications such as infection, nonunion, or joint stiffness.

If you or a loved one has suffered a serious injury or suspect a femur fracture, seek immediate medical attention. For comprehensive diagnosis, surgical care and a personalised recovery plan, schedule a consultation with us today.

Conditions We Treat

Frequently asked questions

How soon will I be able to walk again after a femur fracture?

Recovery times vary, but many patients begin walking with support such as crutches or a walker within a few days after surgery, gradually progressing to full weight-bearing over several months with physiotherapy.

Will I need another surgery after my initial femur fracture repair?

Most patients only require one operation, but a second surgery may be needed if there are complications such as poor bone healing, implant irritation, or malalignment.

What types of pain management are used after a femur fracture?

Pain control may include oral painkillers, nerve blocks, or anti-inflammatory medication, often combined with early mobilisation and physiotherapy to speed recovery.

How long does it take for a femur fracture to heal fully?

The bone typically heals in 4–6 months, but regaining full muscle strength, balance and normal walking patterns can take up to a year.

Is physical therapy essential after a femur fracture?

Yes, physiotherapy is critical for restoring joint movement, muscle strength and gait. It also reduces the risk of stiffness and improves long-term outcomes.

Can a femur fracture cause permanent mobility issues?

Some patients, particularly those with severe injuries or complications, may have lasting stiffness, weakness, or difficulty with certain activities, though most recover good function with proper treatment.

Will a metal implant from a femur fracture repair need to be removed?

In most cases, implants can remain indefinitely without causing problems. Removal is only considered if the hardware causes pain, infection, or other issues.

Can a femur fracture trigger arthritis later in life?

Yes, fractures involving the hip or knee joint surfaces can increase the risk of post-traumatic arthritis years later, especially if joint alignment isn’t fully restored.

How soon can I drive after a femur fracture?

Driving is usually possible once you can fully control your leg without pain or weakness, often 8–12 weeks post-surgery, but this varies and should be confirmed by your surgeon.

Can I return to sports after a femur fracture?

Many patients return to sports within 6–12 months, depending on the type of sport, fracture severity and progress in rehabilitation.