MCL/LCL Injury

Our knees are a powerhouse, bearing our weight and providing flexibility that allow us to move everyday. This stability is provided by two essential ligaments — the Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) and Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL).

MCL and LCL injuries can range from strains to tears. This article covers everything from underlying causes and symptoms to the possible treatment options to recovery and getting back to your peak performance.

MCL and LCL injuries are common sports injuries that require targeted treatment and proper recovery.

The Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) and Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL)

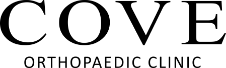

The following structures maintain rotation and stability of the knee:

- Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) — The MCL consists of superficial and deep ligaments that connect the medial femoral epicondyle to the medial condyle of the tibia. The primary function of the MCL is to resist valgus stress and provide rotational stability [1].

- Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) — The LCL is a narrow ligament that connects the femoral epicondyle to the medial fibular head. The primary function of the LCL is to resist various stresses [1].

What are MCL and LCL injuries?

MCL and LCL injuries are typically caused by sudden force or pressure, or twisting motions to the knee. Severity of the injuries can be classified as grades 1 to 3:

|

Severity of Injury |

Description |

|

Grade 1 |

Grade 1 MCL/LCL tears are mild, with slight tearing of the ligament. MRI imaging might indicate fluid surrounding the ligaments [2]. You might feel mild pain and tenderness on the injured knee, with no instability of the knee [3]. |

|

Grade 2 |

Partial tear of the ligament is expected in grade 2 MCL/LCL injuries. There might be increased oedema, as well as pain and tenderness on the knee. |

|

Grade 3 |

Grade 3 is considered a severe injury with complete tearing of the ligaments, and increased oedema. Pain will be intense in grade 3 injuries. The knee will also present laxity when valgus or varus stress is applied [3]. |

Symptoms of MCL and LCL injuries

Common symptoms of a knee ligament injury include:

- Pain

- Swelling

- Tenderness

- Bruising

- Instability on the injured knee

What causes MCL and LCL injuries?

Generally, MCL injuries are more common than LCL injuries. Common causes for MCL Injuries include:

- Sudden shift in direction

- Blows to the knee from the outside (e.g. from tackling)

- Squatting

- Lifting heavy objects

- Awkward or unstable landing after a jump

- Overstretching

- Repeated pressure or stress to the knee

Although LCL injuries are less common, damage to the LCL is usually accompanied by other injuries of neighbouring posterolateral structures [1]. Common causes for LCL Injuries include:

- Bending

- Hard blows or contact to the knee

- Sudden change in direction

- Twisting

- Jumping

- Jerky movements

The nature of these movements can exert a lot of stress on the ligaments because the movement may introduce tension to the ligaments by application of unnatural motions or impact [2].

Who is at risk for MCL and LCL injuries?

People who play dynamic sports such as football, skiing, martial arts, or rugby are most at risk for MCL and LCL injuries.

Ultrasound imaging provides a quick, non-invasive way to accurately diagnose MCL and LCL injuries.

Diagnosis of MCL and LCL injuries

The diagnosis of a MCL/LCL injury usually involves the physician evaluating your symptoms and medical history. Your doctor may also perform several physical tests such as the valgus stress test for MCL injury evaluation, and varus stress test or varus thrust gait for LCL injuries [1].

Imaging tests may be done to visualise the extent of damage, damage of other soft tissues, bone fracture or fluid build-up [2]:

- X-ray — X-rays are usually ordered to identify bone fractures.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) — An MRI scan will help your doctor identify the damaged ligament, as well as any other damage to the surrounding soft tissues or bones.

- Ultrasound — Similar to MRIs, ultrasounds can aid in observing the damage to the ligament and soft tissues. Ultrasounds can also be used to identify any oedema [2].

Differentiating between MCL, LCL and other knee ligament injuries

MCL and LCL are ligaments on the side of the knee that connect the femur to the tibia. Common knee ligament injuries are:

- Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) — The anterior cruciate ligament is one of the two cruciate (forming an “X” cross) ligaments that connect the femur to the tibia. The function of the ACL is to stabilise the knee, preventing excessive forward movement and rotation.

- Posterior cruciate Ligament (PCL) — The posterior cruciate ligament is the other cruciate ligament that stabilises the knee, preventing the tibia from sliding too far backward under the femur.

- Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) — MCL is the ligament that connects the femur to the tibia on the inside of the knee, stabilising the knee and preventing it from moving inward.

- Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) — LCL is the ligament that connects the femur to the tibia on the outside of the knee, stabilising the knee and preventing excessive side-to-side movement.

When you feel a ligament injury, you may not be able to tell which ligament is injured. Your physician will then perform different physical tests that can identify which ligament is injured based on the movements of these tests [1].

Treatment of MCL and LCL injuries

Depending on the extent of the injury, non-surgical and surgical treatments are available. Minor injuries of grade 1 or 2 can heal well with non-surgical management [3]. These include:

Conservative Treatments

- RICE method — RICE stands for Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation. These steps are crucial in reducing pain and swelling caused by the injury.

- Pain relief — Taking prescription non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can relieve pain and inflammation

- Knee brace — Wearing a knee brace will limit movement to improve healing of the ligament.

- Crutches — The use of crutches can keep weight off the knee to improve recovery.

- Physical therapy — Rehabilitation via physical therapy can help you regain strength and function of your leg.

Surgical Treatments

In more serious injuries, your doctor may require surgery to reconstruct or reattach the torn ligament. Furthermore, damage to other soft tissues or structures may also warrant surgical intervention.

- Sutures — Different types of sutures can be used to stitch together torn ligaments to the bone [4].

- Screw fixation — Screw fixation is typically used in bony avulsions, where the ligaments may still be intact [5].

- Reconstruction surgery — In reconstruction surgeries, the doctor will take grafts from tendons of the patella or hamstring from the patient. This is called an autograft. In some cases allografts (taken from a donor) are used.

Rehabilitation Process

Rehabilitation and strength training are also a part of conservative treatment without surgery [5]. However, post-operative rehabilitation is often recommended to gradually regain strength and movement in patients following a long recovery period.

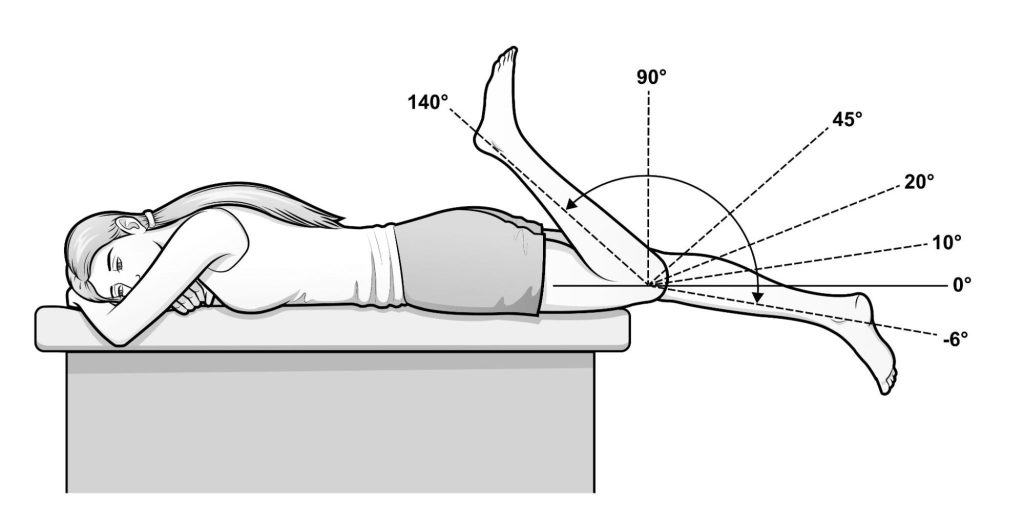

- Hinged knee brace — The use of a hinged knee brace is common for at least 4 to 6 weeks post-surgery, the flexion angle is slowly reduced over this period of time [6].

- Weight-bearing — Weight-bearing exercises are important for improving the strength of the leg, and usually starts when the knee flexion reaches 15 degrees [6].

- Range of motion (ROM) — ROM exercises train the knee to regain flexion and extension abilities. This can later be combined with weight-bearing [6].

Knee range of motion exercises are crucial in restoring flexibility and strength during LCL and MCL recovery.

Get in touch with us to schedule an appointment if you have concerns with MCL or LCL injuries. Our dedicated doctors are available to address your concerns and provide you with patient-centric care.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I prevent knee ligament injuries?

While we cannot possibly predict when a knee injury will occur, preventive measures can reduce the risk and limit the severity of injury. These include:

- Wearing a knee brace when playing sports

- Doing stretches or warm up exercises before playing sports

- Get into exercises that improve balance, strength, and mobility.

How long does a full recovery take?

Recovery depends on the severity of injuries, generally:

- Grade 1 injuries – 1 to 4 weeks

- Grade 2 injuries – 4 to 12 weeks

- Grade 3 injuries – 6 to 12 weeks or more

Healing times for surgical procedures will also vary for each individual and the type of injuries or surgeries they had. Ask your doctor about the recovery periods for surgical procedures.

Will past injuries increase risks of MCL or LCL injuries?

Yes, past injuries will increase the risk of MCL or LCL tears due to various issues, such as weakened ligament structures or muscle imbalances. Hence, it is important to take extra precaution if you have a history of injuries. Always consult your doctor first before returning to any sports that might cause re-injury.

Can ligament tears heal on their own?

Minor tears can heal on their own, but this largely depends on the severity of the injury and the specific ligament involved. Rehabilitative measures are recommended to ensure proper healing.

Can you injure both the MCL and LCL at the same time?

Injuring multiple ligaments at the same time can happen. More often the ligaments closer to each other may tear at the same time. For example, in about 78% of grade 3 MCL tears, the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is also injured [1].

Are MCL and LCL injuries common in sports?

Yes, MCL and LCL injuries are quite common in sports that involve quick changes in direction, twisting and impact to the knee. MCL injuries are more common in activities like football or rugby, while LCL injuries are more common in basketball, skiing and hockey.

How can I tell if I require MCL/LCL surgery?

Surgery is often indicated for injuries that do not get better with conservative treatment. Most MCL injuries can heal with conservative treatment alone, but you may not know how severe the injury may be without prior consultation or assessment.

The best course of action is to consult a doctor or an orthopaedic surgeon to examine and evaluate your injury. They will also be able to tell whether your injuries require surgery.

References

- Bronstein RD, Schaffer JC. Physical Examination of Knee Ligament Injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017 Apr;25(4):280-287. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00463. PMID: 28291144.

- Grawe B, Schroeder AJ, Kakazu R, Messer MS. Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury About the Knee: Anatomy, Evaluation, and Management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2018 Mar 15;26(6):e120-e127. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00028. PMID: 29443704.

- Wijdicks CA, Griffith CJ, Johansen S, Engebretsen L, LaPrade RF. Injuries to the medial collateral ligament and associated medial structures of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010 May;92(5):1266-80. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01229. PMID: 20439679.

- Lubowitz JH, MacKay G, Gilmer B. Knee medial collateral ligament and posteromedial corner anatomic repair with internal bracing. Arthrosc Tech. 2014 Aug 11;3(4):e505-8. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2014.05.008. PMID: 25276610; PMCID: PMC4175550.

- Tandogan NR, Kayaalp A. Surgical treatment of medial knee ligament injuries: current indications and techniques. EFORT Open Rev. 2017 Mar 13;1(2):27-33. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.1.000007. PMID: 28461925; PMCID: PMC5367556.

- Vosoughi F, Rezaei Dogahe R, Nuri A, Ayati Firoozabadi M, Mortazavi J. Medial Collateral Ligament Injury of the Knee: A Review on Current Concept and Management. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2021 May;9(3):255-262. doi: 10.22038/abjs.2021.48458.2401. PMID: 34239952; PMCID: PMC8221433.