Partial Knee

Replacement

- Home

- Conditions We Treat

- Knee

- Partial Knee Replacement

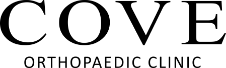

Partial knee replacement, or unicompartmental knee replacement (UKR), is a procedure designed for patients whose arthritis is limited to a single part of the knee, most often the medial (inner) compartment. Unlike a total knee replacement, which resurfaces the entire joint, this operation targets only the damaged area while preserving the remaining healthy bone, cartilage, and stabilising ligaments such as the cruciates.

Because more of the natural knee is left intact, patients may benefit from a smaller incision, less blood loss, quicker rehabilitation, and a joint that feels closer to their own. The procedure is most successful in people with disease confined to one compartment, good ligament stability and a maintained range of motion. Careful patient selection is essential, as those with widespread arthritis or severe deformity are better suited for total knee replacement.

Anatomy of the midfoot

The midfoot is formed by the three cuneiform bones and the cuboid, which articulate with the five metatarsals at the Lisfranc joint. This joint is divided into three functional columns:

- Medial column — the first metatarsal and medial cuneiform.

- Central column — the second and third metatarsals with the intermediate and lateral cuneiforms.

- Lateral column — the fourth and fifth metatarsals with the cuboid.

A complex arrangement of tarsometatarsal, intermetatarsal and intertarsal ligaments provides stability to these articulations, while allowing controlled movement. Together, these structures maintain the integrity of the foot arch and bear the body’s weight during gait.

Types of midfoot fractures

Midfoot fractures, especially those involving the Lisfranc joint, may present in several patterns depending on the direction and force of injury:

- Avulsion fractures — a small fragment of bone is pulled away where a ligament attaches, usually due to twisting or indirect force.

- Shear (split) fractures — the bone splits when opposing forces act on its surfaces. These may occur in the coronal (front-to-back) or sagittal (side-to-side) plane.

- Impaction fractures — the bone ends are compressed or “driven into” one another. This may involve one joint (uniarticular) or extend across multiple joints (biarticular) in high-energy injuries.

These patterns can involve several bones of the midfoot, including the cuboid, cuneiforms and navicular. Injuries often affect multiple bones at once. The medial cuneiform and the base of the second metatarsal are particularly vulnerable, as they form the central stabilising point of the Lisfranc joint.

Clinical classification systems

In clinical practice, surgeons often use the Hardcastle and Myerson classification to describe Lisfranc injuries more precisely:

- Type A — total incongruity, where all the metatarsals are displaced in the same direction.

- Type B — partial incongruity, where only some metatarsals are displaced.

- Type C — divergent, where the metatarsals are displaced in different directions.

This system helps guide treatment decisions and prognosis, especially in complex or high-energy injuries.

What is partial knee replacement?

A partial knee replacement resurfaces only the damaged part of the joint, preserving healthy bone, cartilage and ligaments. The main types include:

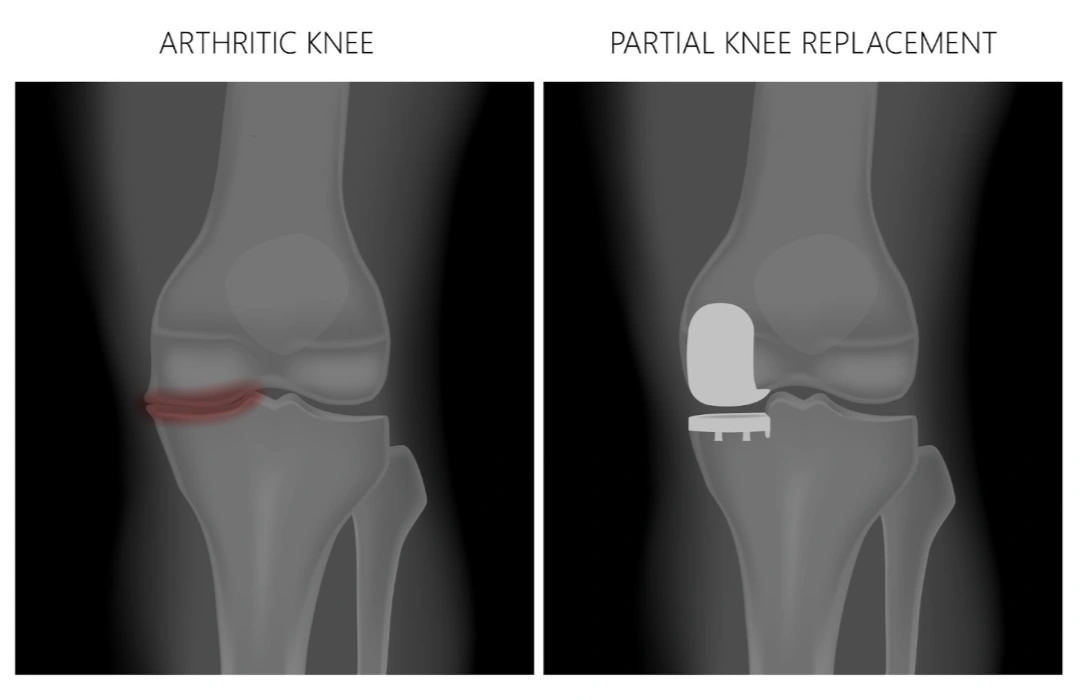

Unicompartmental knee replacement (UKR)

This is the most frequently performed type of partial knee replacement. It is used when arthritis or damage is limited to one compartment of the knee, most commonly the medial (inner) side, though it can also be performed on the lateral (outer) side. During surgery, only the worn cartilage and a thin layer of underlying bone are removed and replaced with metal and plastic components. Because the rest of the joint, including the cruciate ligaments, remains intact, the knee often retains a more natural movement compared with a total knee replacement.

Patients undergoing UKR generally benefit from a smaller incision, reduced blood loss, less postoperative pain, and a shorter hospital stay. They also tend to recover faster and regain function earlier. However, long-term data show a slightly higher chance of revision compared with total knee replacement, mainly because arthritis may later develop in the unaffected compartments.

Patellofemoral replacement

Also known as patellofemoral arthroplasty, this procedure is designed for patients whose arthritis is confined to the joint between the kneecap (patella) and the thigh bone (femur). It is less commonly performed than UKR but can be highly effective in the right patients. The operation involves resurfacing the underside of the patella and the corresponding groove on the femur with prosthetic components. This relieves pain caused by patellofemoral arthritis while leaving the tibiofemoral compartments untouched.

Patellofemoral replacement is most successful in patients who have clear, isolated disease, intact ligaments, and no significant deformity or arthritis elsewhere in the knee. If arthritis progresses to other compartments later, the implant can often be revised to a total knee replacement.

Bicompartmental replacement

This procedure is an option for patients with disease affecting two compartments of the knee, most often the medial and patellofemoral compartments. It is less common than unicompartmental replacement but may provide a middle ground between partial and total replacement. In bicompartmental replacement, both affected areas are resurfaced with implants, while the remaining healthy compartment and stabilising ligaments are preserved. The goal is to relieve pain, restore function and maintain as much of the natural joint as possible.

Because more of the knee is resurfaced compared with UKR, the recovery may be slightly longer, but patients still benefit from bone preservation, better joint kinematics and the possibility of easier revision to total knee replacement if needed in the future.

How does partial knee replacement differ from total knee replacement?

Both partial and total knee replacement are established treatments for advanced knee arthritis, but they differ in scope and suitability.

- Partial knee replacement — only the diseased compartment of the knee is resurfaced, most often the medial side but sometimes the lateral or patellofemoral joint. Bicompartmental replacement may be used when two areas are involved. Because the cruciate ligaments and unaffected bone are preserved, patients often experience a more natural-feeling joint, quicker rehabilitation, and a smaller incision. The main limitation is that if arthritis progresses in the remaining compartments, further surgery may be required.

- Total knee replacement — the entire joint is resurfaced, including the medial and lateral condyles, tibial plateau, and patellofemoral joint. It is preferred when arthritis is widespread or when deformity and instability make a partial replacement unsuitable.

Neither operation is automatically superior. The right choice depends on the extent of joint damage, ligament stability, age, activity level, and personal goals. Patients who qualify for partial replacement often value the faster recovery and greater range of motion it can provide, while those with more advanced disease usually benefit more from a total replacement.

Partial vs Total Knee Replacement

| Feature | Partial Knee Replacement | Total Knee Replacement |

|---|---|---|

| Extent of surgery | Resurfaces only the affected compartment (medial, lateral or patellofemoral) | Resurfaces all three compartments of the knee |

| Structures preserved | Cruciate ligaments and healthy bone remain intact | Cruciate ligaments often sacrificed; all surfaces replaced |

| Incision and recovery | Smaller incision, less blood loss, quicker early recovery | Larger incision, longer rehabilitation period |

| Function and feel | Often feels more natural, with better early range of motion | Reliable pain relief, but joint mechanics less “natural” |

| Risk of revision | Higher chance of revision if arthritis develops in other compartments | Lower revision rates in the long term |

| Best suited for | Localised arthritis with stable ligaments and preserved motion | Widespread arthritis, severe deformity, or ligament insufficiency |

What conditions may require a partial knee replacement?

Partial knee replacement is considered when arthritis or damage is confined to a specific compartment of the knee. The main conditions include:

- Osteoarthritis — the leading indication for partial knee replacement. In osteoarthritis, the protective cartilage covering the joint surfaces gradually wears away, causing pain, stiffness, and swelling. It most often affects older adults, though younger patients with localised disease may also be candidates.

- Post-traumatic arthritis — this develops after an injury to the knee, such as a fracture, ligament rupture, or sports trauma. The injury alters joint alignment and cartilage health, eventually leading to arthritis in the affected area. If damage remains localised, partial knee replacement can provide relief while preserving the rest of the joint.

- Avascular necrosis (osteonecrosis) — loss of blood supply to part of the knee, usually the medial femoral condyle, can cause localised bone collapse and secondary arthritis. Partial replacement may be used if the disease is limited in scope.

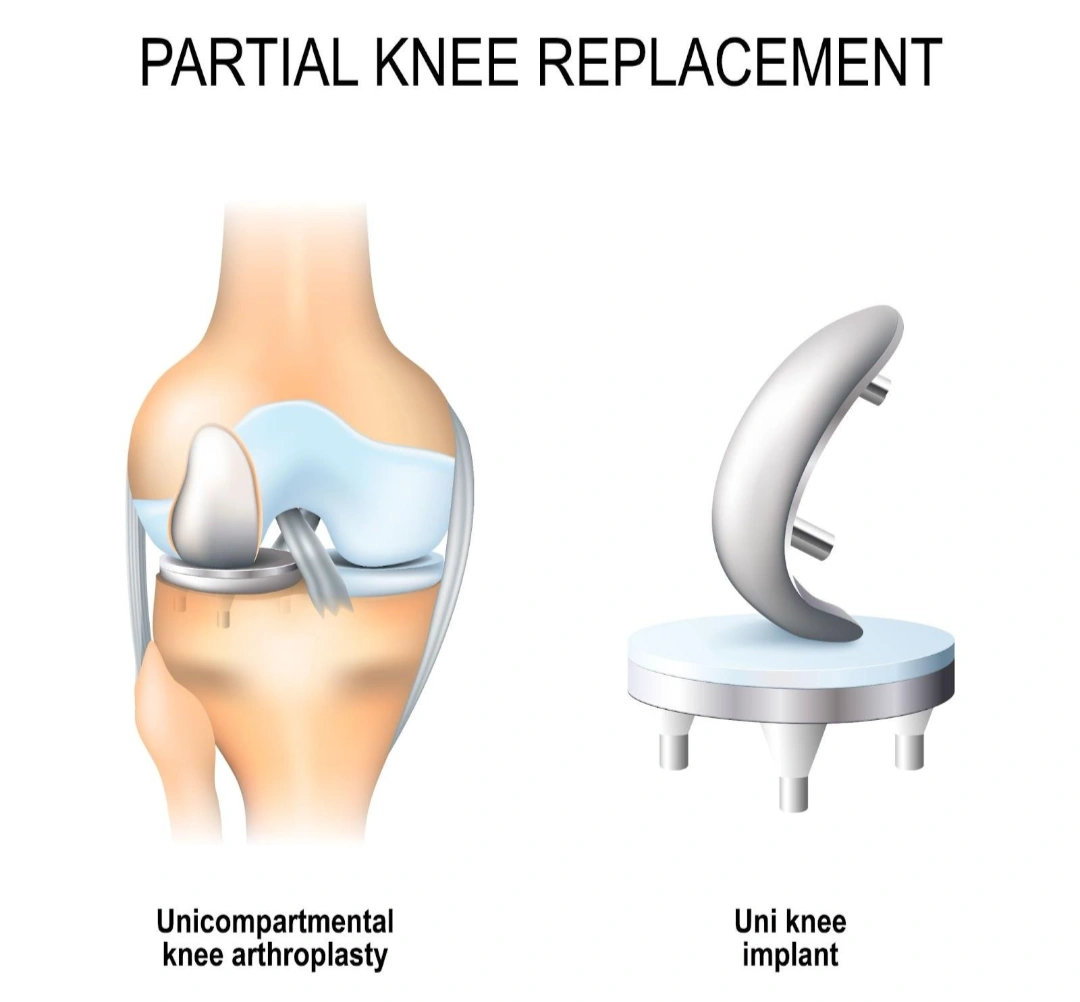

- Meniscal deficiency with compartmental wear — following removal of a meniscus (meniscectomy), arthritis may develop in that compartment alone. In select cases, partial replacement can restore function and reduce pain.

- Failure of previous joint-preserving surgery — patients who have undergone cartilage restoration procedures or osteotomies and later develop localised arthritis may be considered for partial knee replacement if disease is confined to one or two compartments.

Patients with advanced arthritis affecting multiple compartments, severe deformity, or significant ligament instability are usually advised to undergo a total knee replacement instead, as partial replacement would not adequately address their condition.

How do I know if I am suitable for a partial knee replacement?

Not every patient with knee arthritis is an ideal candidate for a partial knee replacement. Success depends on several clinical and lifestyle factors, which your orthopaedic surgeon will assess carefully:

- Age — there is no strict age limit, but younger patients often prefer partial replacement to maintain more natural knee function. However, because implants have a finite lifespan, younger and more active individuals face a higher chance of requiring revision surgery later in life.

- Severity and location of damage — partial replacement is only appropriate when arthritis is confined to a single compartment (or two in bicompartmental replacement) with intact ligaments. If the disease progresses to other compartments, a total knee replacement may eventually be necessary.

- Activity level — patients with moderate activity levels often do well with partial replacement, enjoying better mobility and function. High-impact activities, however, can increase the risk of implant wear and shorten its lifespan.

- BMI and overall health — excess weight places added stress on the joint and can compromise outcomes. While higher BMI is not an absolute contraindication, it is a relative risk factor and must be considered alongside other health conditions.

- Cost considerations — partial knee replacement is usually less costly than total replacement. For some patients, affordability may influence their choice, though medical suitability remains the most important factor.

Suitability for partial knee replacement is determined by a combination of clinical findings, imaging results, and lifestyle goals. A comprehensive consultation with your orthopaedic specialist is essential to weigh the risks and benefits and decide whether partial or total knee replacement is the best option for you.

What are the benefits of a partial knee replacement?

Partial knee replacement offers several advantages when compared with total knee replacement, particularly in carefully selected patients:

- Smaller incision and less invasive surgery — only the damaged compartment is resurfaced, which means less disruption to healthy bone, cartilage and surrounding tissues.

- Preservation of ligaments and bone — unlike total knee replacement, the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) are usually preserved. This helps the knee move and feel more natural after surgery.

- Faster recovery and rehabilitation — patients often mobilise sooner, spend less time in hospital, and regain function earlier because less tissue has been disturbed.

- More natural joint function — preserving healthy structures allows better range of motion, improved knee stability, and a gait pattern that feels closer to the patient’s own knee.

- Lower risk of certain complications — risks such as major blood loss, infection, or significant post-operative stiffness may be reduced compared with total knee replacement.

- Easier revision if required later — because more of the natural bone and ligaments are preserved, conversion to a total knee replacement in the future is usually less complex than revising a previous total knee replacement.

What are the risks associated with partial knee replacement?

As with any major surgery, partial knee replacement carries certain risks and potential complications. These include:

- Blood clots — reduced mobility after surgery can increase the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism. Preventive measures such as early mobilisation, compression stockings, and prescribed blood-thinning medication help lower this risk.

- Infection — both superficial wound infections and deeper joint infections can occur, though the latter are rare. Deep infections are serious and may require further surgery, including implant removal.

- Nerve or vessel injury — rarely, nerves or blood vessels near the joint may be injured during surgery. More commonly, patients may experience temporary numbness or tingling around the incision site.

- Implant-related problems — over time, the prosthesis may loosen, wear, or shift, particularly if the joint alignment is poor or arthritis progresses in other compartments.

- Joint stiffness — scar tissue (arthrofibrosis) may develop inside the joint, limiting flexibility and movement. Early physiotherapy and pain control are essential to minimise this risk.

- Need for revision surgery — some patients may later require revision surgery if complications develop or if arthritis spreads to untreated parts of the knee. This may involve converting the partial replacement to a total knee replacement.

While these risks exist, most patients undergo partial knee replacement without major complications, especially when surgery is performed by an experienced orthopaedic team and rehabilitation protocols are followed closely.

What happens during partial knee replacement surgery?

Partial knee replacement is considered when arthritis is confined to one part of the joint and conservative treatments no longer provide relief. The process usually involves several stages:

- Consultation — your surgeon will first confirm that only certain compartments of the knee are affected and that ligaments remain stable. They will explain the procedure in detail, including its risks, benefits, and expected outcomes. This is also your opportunity to ask any questions about recovery, activity restrictions, or alternatives.

- Preparation — imaging studies such as X-rays or MRI scans are used to plan the surgery and identify the exact area to be resurfaced. You may be asked to fast from midnight before surgery. It is important to inform your care team about any medical conditions, medications, or allergies so they can take the necessary precautions.

- Anaesthesia — on the day of surgery, you will receive either spinal or general anaesthesia, depending on your medical profile and anaesthetist’s recommendation. You will be closely monitored throughout.

- Surgery — a smaller incision is made compared with total knee replacement. The surgeon removes the damaged cartilage and a thin layer of bone in the affected compartment, which is then resurfaced with metal and plastic components precisely sized to your joint. The surrounding ligaments and healthy compartments are preserved, allowing the knee to maintain more natural movement.

Non-surgical treatment — when the injury is stable

Non-surgical treatment is considered when the midfoot fracture is stable and properly aligned, meaning the bones have not shifted out of place. This usually applies to nondisplaced fractures, stress-related fractures, or low-energy injuries that do not disrupt the midfoot joints. In such cases, the injury can often heal successfully with immobilisation and careful monitoring rather than surgery.

- Immobilisation — immobilisation keeps the foot protected while the fracture heals naturally. A below-knee cast or walker boot is applied with strict non-weight-bearing for around 6 weeks, followed by protected weight-bearing in a boot for another 4–6 weeks.

- Rehabilitation — rehabilitation ensures that stiffness is minimised and function is restored. Early ankle and toe movements may be introduced, progressing to strengthening and gait training once partial weight-bearing is allowed.

- Symptom control — pain and swelling are managed to improve comfort and recovery. This includes rest, elevation, ice and appropriate pain relief such as paracetamol or NSAIDs, taken under medical guidance.

Surgical treatment — when the injury is unstable or displaced

Surgery is required when the injury involves displacement, instability or arch collapse, as anatomical realignment is critical to prevent long-term arthritis.

- Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) — ORIF restores the bones to their correct alignment using screws, plates or both. The aim is to achieve precise reduction of the tarsometatarsal joints and maintain stability during healing.

- Primary arthrodesis (fusion) — primary arthrodesis eliminates joint movement by fusing affected bones. This is often used for severe ligamentous injuries, comminuted fractures or late presentations where stability cannot be achieved with fixation alone.

- Percutaneous fixation — percutaneous fixation provides stabilisation through small incisions. Screws or K-wires are inserted with minimal soft tissue disruption, often as a temporary measure in simpler or reducible injuries.

- Dorsal plating — dorsal plating adds stability in complex fracture-dislocations. A plate is applied to the top of the midfoot to maintain reduction, particularly when screws alone are insufficient.

- Wire fixation — wire fixation uses temporary Kirschner wires (K-wires) to hold bone fragments. They may be used alone in simple cases or as part of an ORIF procedure when additional stability is needed.

- External fixation — external fixation provides temporary stabilisation in severe trauma. It is typically used when there is significant swelling or soft tissue damage before definitive surgery is performed.

Aftercare and recovery — what to expect

After treatment, recovery requires structured protection and physiotherapy to regain mobility.

- Post-operative protection — patients remain non-weight-bearing for 6–8 weeks, then gradually progress to partial and full weight-bearing as advised.

- Hardware removal — some implants, such as transarticular screws or temporary wires, are removed once healing is secure, usually around 4–6 months.

- Rehabilitation — physiotherapy focuses on restoring strength, balance and gait. Exercises are adjusted depending on whether joints were fused or fixed.

- Return to activity — daily activities usually resume within 3–4 months, while return to sports may take 6–12 months depending on severity and treatment type.

What happens after partial knee replacement?

Recovery begins immediately after surgery and continues for several months:

- Hospital stay — many patients are discharged within 1–3 days, although some centres offer same-day discharge under enhanced recovery protocols.

- Physiotherapy — rehabilitation starts soon after surgery. Guided exercises help restore flexibility, rebuild muscle strength, and improve walking ability. Patients often recover faster than after total knee replacement because more of the natural joint is preserved.

- Rehabilitation timeline — most patients can resume everyday activities within 6–12 weeks, though full recovery and strengthening may continue for up to a year. Low-impact activities such as swimming or cycling are usually encouraged; high-impact sports are not recommended.

- Follow-up — regular appointments are scheduled to check the implant and monitor your progress. If pain, stiffness, or instability occurs, earlier review is advised. In some cases, revision surgery may be required if arthritis develops in the remaining compartments or if implant problems arise.

What can I do to speed up recovery after a partial knee replacement?

Your recovery after partial knee replacement depends not only on the surgery itself but also on how actively you participate in your rehabilitation. The following steps can support a smoother and more effective recovery:

- Follow your physiotherapy programme — regular exercises to restore strength, balance, and flexibility are essential. Skipping physiotherapy can lead to stiffness and slower progress.

- Manage pain and swelling — take pain relief as prescribed, use ice packs, and elevate your leg when resting. Effective pain control will allow you to move and exercise more comfortably.

- Look after your wound — keep the incision clean and dry. Change dressings as instructed and report any signs of infection, such as redness, swelling, or discharge.

- Stay mobile — start walking with the support of crutches or a walker as advised. Gradually increase your walking distance each day to build stamina and confidence.

- Maintain a healthy lifestyle — eating a balanced diet rich in protein, vitamins, and minerals supports healing. Keeping your weight within a healthy range reduces stress on your new joint.

- Avoid high-impact activities — stick to low-impact exercises such as swimming, cycling, or walking during recovery. Running and jumping should generally be avoided to protect the implant.

- Attend follow-up appointments — regular check-ups allow your surgeon to monitor healing and the stability of the prosthesis, and to address any concerns early.

Staying consistent with your rehabilitation plan and following your medical team’s advice will help you regain mobility faster and achieve the best long-term results from your partial knee replacement.

Summary

Partial knee replacement, also called unicompartmental knee replacement, is a surgical option for patients with arthritis or damage limited to one part of the knee. Unlike total knee replacement, it resurfaces only the affected compartment while preserving healthy bone, cartilage, and ligaments, which allows the knee to retain more natural movement. Depending on the pattern of disease, patients may undergo a unicompartmental, patellofemoral, or bicompartmental replacement.

For the right candidate, benefits include a smaller incision, faster recovery, better range of motion, and easier revision in the future if needed. However, not everyone is suitable — advanced arthritis, severe deformity, or unstable ligaments often require a total knee replacement instead. As with any surgery, risks such as blood clots, infection, implant problems, or stiffness must be considered, and success depends on careful patient selection and dedicated rehabilitation afterwards.

If you are struggling with persistent knee pain and want to explore whether a partial knee replacement is right for you, schedule a consultation with Cove Orthopaedics for a thorough assessment and a tailored treatment plan.

Frequently asked questions

How long does a partial knee replacement last?

Most implants last 15–20 years, depending on age, activity level, weight, and overall health. Regular follow-up helps detect problems early.

Is partial knee replacement better than total knee replacement?

Neither is universally better. Partial replacement suits patients with arthritis confined to one area, while total replacement is recommended for widespread disease.

What is the recovery time for partial knee replacement?

Many patients resume daily activities in 6–12 weeks, though full recovery and strengthening may take up to a year.

Can you walk normally after a partial knee replacement?

Yes. Most patients walk with support within a few days and regain a near-normal gait after completing physiotherapy.

Is partial knee replacement painful?

Some pain and swelling are expected initially, but this is managed with medication, ice, and physiotherapy. Most patients report significant pain relief once healed.

What is the success rate of partial knee replacement?

Studies show success rates above 90% at 10 years when performed on carefully selected patients by experienced surgeons.

When can I return to work after partial knee replacement?

For office jobs, many return in 3–6 weeks; physical or labour-intensive jobs may require several months.

When can I drive after partial knee replacement?

Patients usually resume driving at 4–6 weeks once they have good control of the operated leg and clearance from their surgeon.

Can I play sports after a partial knee replacement?

Low-impact activities like swimming, cycling, and golf are encouraged. High-impact sports such as running or basketball are generally discouraged to protect the implant.

Is partial knee replacement suitable for young patients?

Yes, but younger patients may require revision later in life. Suitability depends more on the extent of arthritis and ligament health than age alone.

Am I too old for a partial knee replacement?

There is no strict upper age limit. If arthritis is localised and general health allows surgery, older patients can still benefit.

Can partial knee replacement be revised to a total knee replacement?

Yes. If arthritis progresses in other compartments or the implant fails, the procedure can be converted to a total knee replacement.

How much does partial knee replacement cost in Singapore?

Costs vary depending on hospital, surgeon, and implant type, but it is generally less expensive than a total knee replacement.

Is partial knee replacement done under general anaesthesia?

It can be done under general or spinal anaesthesia. The anaesthetist will choose the safest option for your health.

What are the risks of partial knee replacement?

Risks include infection, blood clots, stiffness, nerve injury, implant loosening, and the need for revision surgery in the future.

How do I know if I am a candidate for partial knee replacement?

You may be suitable if arthritis is confined to one compartment, ligaments are intact, and you have good knee motion. A specialist assessment is essential.

Can overweight patients have partial knee replacement?

Yes, but higher body weight can increase stress on the implant and affect long-term outcomes. Suitability is assessed individually.

How soon can I climb stairs after partial knee replacement?

Most patients can manage stairs with support within a few weeks, improving as strength and balance return.

What is the difference between partial and total knee replacement recovery?

Recovery from partial replacement is generally faster, with less pain and earlier return to daily activities compared with total replacement.

Does partial knee replacement feel like a natural knee?

Many patients say it feels closer to a normal knee than total replacement because ligaments and healthy bone are preserved.

Conditions We Treat